Cool Computing: MIDAC To MTS To CAEN

The goal was straightforward, but the path to building the nation’s most sophisticated engineering-based IT system was long and winding.

Enlarge

Enlarge

In the Beginning

The goal was straightforward – to build the most sophisticated information technology environment of any engineering college in the nation. But computers (for computing artillery trajectories) as well as roads (as potential runways) were initially built for national security purposes only. And this particular path would prove to be long and winding.

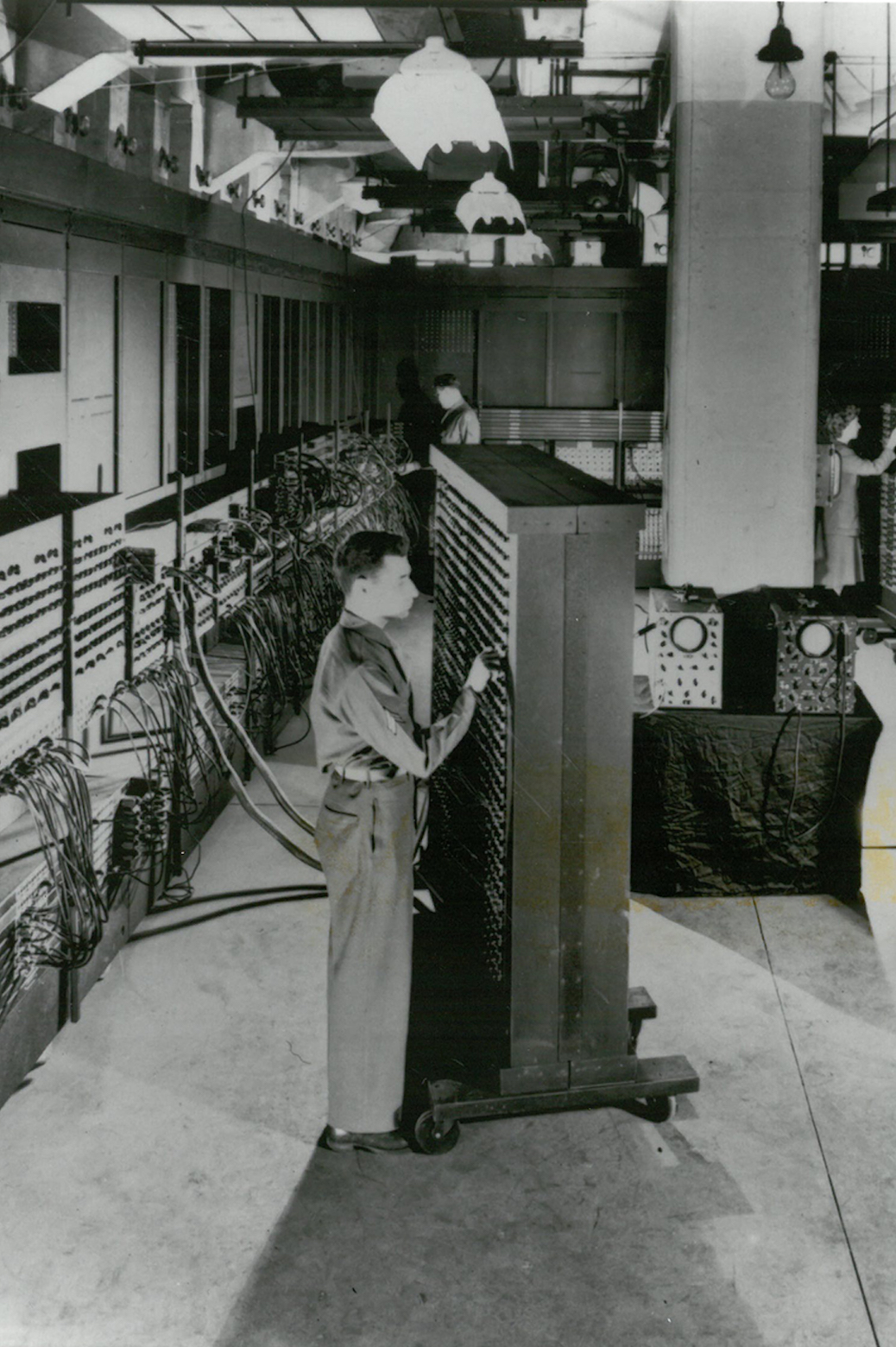

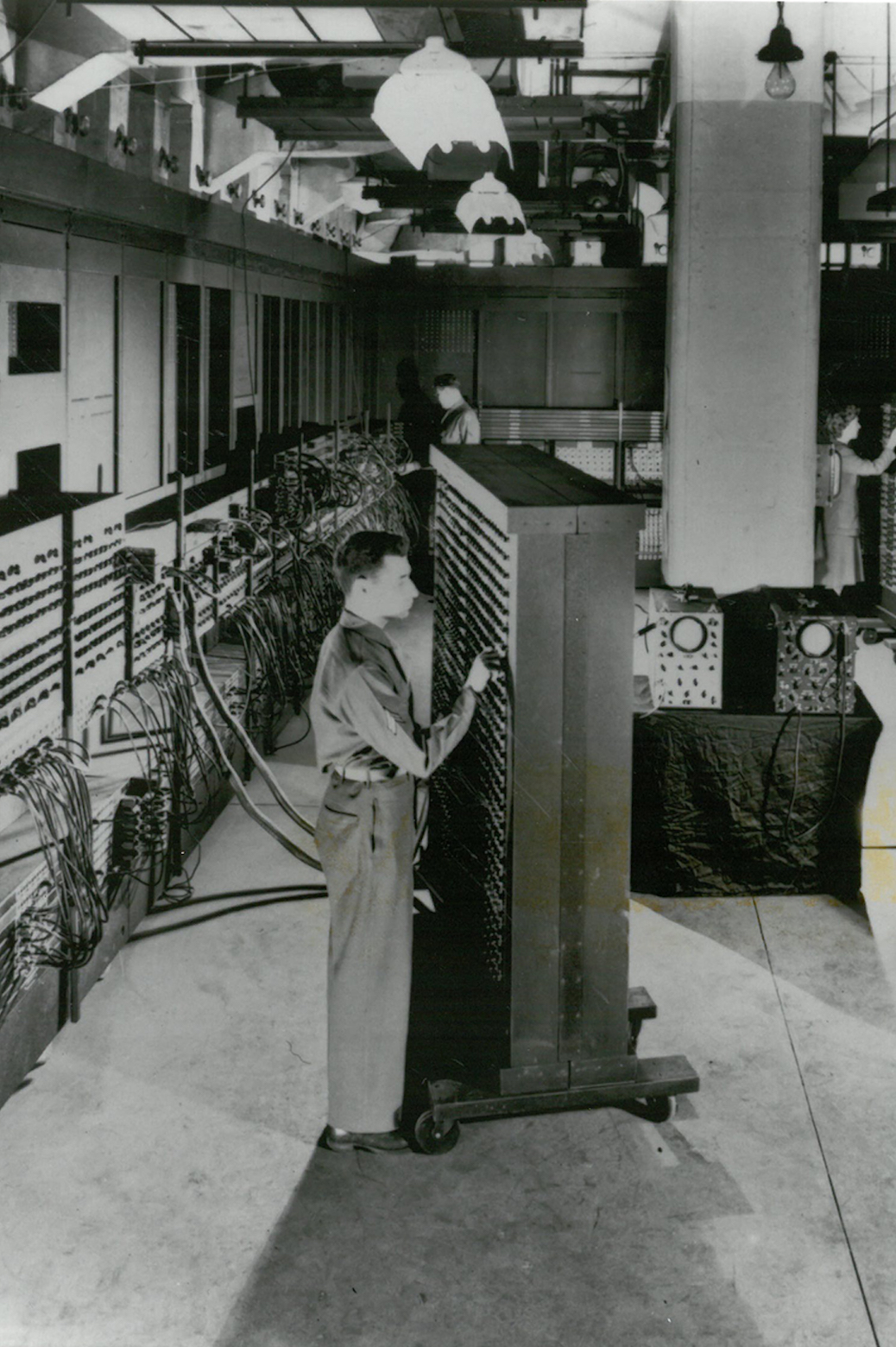

In February 1951, fueled by a collaboration between the Wright Air Development Center and the United States Air Force, the Willow Run Research Center of the University of Michigan’s Engineering Research Institute began to develop the Michigan Digital Automatic Computer (MIDAC). When introducing it to the University of Michigan community, President Harlan Hatcher wrote that MIDAC’s “ultimate purpose is the solution of certain complicated military problems.”

When MIDAC became operational in 1953, it became the sixth digital automatic computer employed at a research university and the first computer of its kind in the Midwest. The University offered two-week computer courses in numerical analysis and computer logic, and 35 people signed up. Its unveiling made the front page of the Chicago Tribune: “Secrecy wraps were removed today from new electronic brain machines which play pool, shoot craps, and curse human opponents who attempt to cheat the mechanical marvels at games of tick-tack-toe.”

Game-playing aside, MIDAC required 12 tons of refrigeration equipment to cool its 500,000 connections and tubes. Its main memory storage device was a rotating magnetic “drum,” which stored just 6,000 “words,” or short segments of data. It was operated by Willow Run’s Digital Computation Department.

Enlarge

Enlarge

“This machine really marked the beginning of the present era.”

One chemical engineering student, Ronald Crozier, used MIDAC as a basis for his Ph.D. thesis in 1956. But by 1958 this fast new machine already had been supplemented by the faster Michigan Digital Special Automatic Computer (MDSAC). James Wilkes, professor emeritus of chemical engineering, and coauthor of Applied Numerical Methods (1969) and Digital Computing and Numerical Methods (1973), enrolled in the first full-term digital computing course at the University of Michigan as a student in 1955.

“This machine really marked the beginning of the present era,” Wilkes says.

Introducing Arthur Burks

After Arthur Burks (PhD Philosophy ‘41) graduated from the University, “the war, of course, was raging in Europe,” he once explained to an interviewer. “And so I thought that I would be better able to contribute to the war effort by getting this training in engineering.”

Burks would attend the Moore School of Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania, where he played a leading role in designing the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC) – the world’s first general purpose electronic digital computer.

“By the time I started the ENIAC, I had had a year and a half of research experience, two years of teaching, and by then I was teaching courses in which I was giving the lectures myself, and I also had the equivalent of a master’s degree in electrical engineering,” Burks recounted.

“There was certainly the idea that this was novel, and we were ahead of everyone else,” Burks said.

The paper’s leaps in logic helped to advance computing from the realm of the calculator to that of the modern computer.

By 1946 Burks would leave Penn to become a faculty member at Michigan, where the philosopher-mathematician co-authored the paper, “Preliminary Discussion of the Logical Design of an Electronic Computing Instrument.” The paper’s leaps in logic helped to advance computing from the realm of the calculator to that of the modern computer by proposing that a series of written instructions could direct a machine to perform conditional actions.

According to former Michigan computer science and psychology professor John Holland, who studied under Burks, computers, such as the ENIAC, used wires plugged into control panels called plugboards. And plugboard computers, in a sense, could not decide what to do next based on the outcomes of earlier calculations.

Enlarge

Enlarge

“That paper is widely recognized as the first paper that really discussed programming,” Holland once said. “With his co-authors John von Neumann and Herman Goldstine, [Burks] really set up the digital age.”

Once he returned to Michigan, Burks taught for four decades, championing the potential of computing long before there were academic departments in computer science. In 1949, he founded a Logic of Computers Group, and in 1957 he started a graduate program in Communication Sciences. The program was a blend of computing, language study, and biology, which addressed challenges such as speech recognition, machine learning, and complex adaptive systems, which was among those later called neural networks.

“Art Burks,” said Holland, “always viewed computing from a very broad, cross-disciplinary perspective.”

MTS: A sense of community

The IBM 360/67 arrived on campus in 1967, and Michigan’s first time-sharing computer system, Michigan Terminal System (MTS), was released to the University.

“It was exciting; it was brand new,” enthuses Jeff Ogden, former senior associate director of the Computing Center.

“Some said, ‘It won’t work.’ Or, ‘It’ll be too expensive.’ Others were proving it would work. It was a rewarding environment,” Ogden says.

MTS provided the U-M community a virtual place for coming together to share data, tools, information, and ideas by sharing programs and data in disk files or on magnetic tapes. They could also use MTS as a home base for sending e-mail, or to participate in group discussions.

“MTS was a tool used by everyone at the University,” says Mike Alexander, one of MTS’s architects. “It got tied into the life and work of the University and became as fundamental as the phone system.”

Users and MTS developers alike were able to collaborate. According to Al Anderson, then an assistant research scientist at U-M’s Population Studies Center, “MTS supported a computing environment and computing community for many years with characteristics that I suspect we will not see or experience again.”

Enlarge

Enlarge

It was a system for everyone, not just those who were traditionally thought to need computing. “MTS let ordinary people do routine things easily,” Anderson says.

“It was ground-breaking,” Ogden says. “And in an industry where systems routinely become obsolete in five years or less, the 30-year life span of MTS is almost unprecedented.”

Bill Joy – perhaps best known for XYZ – was a Michigan Engineering student in the early 1970s. Joy worked at the Computing Center on North Campus, conducting performance measurements and analysis on the MTS file system. In his 2008 book, Outliers – The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell wrote about how Joy’s U-M experience helped him to accumulate the bulk of the 10,000 hours of experience Gladwell claims is necessary to master a field.

“This is where Michigan came in, because Michigan was one of the first universities in the world to switch over to time-sharing,” Gladwell wrote. “By 1967, a prototype of [MTS] was up and running. By the early 1970s, Michigan had enough computing power that a hundred people could be programming simultaneously in the Computing Center. ‘In the late sixties, early seventies, I don’t think there was any place else that was exactly like Michigan,’ said Mike Alexander, one of the pioneers of Michigan’s computing system. ‘Maybe Carnegie Mellon. Maybe Dartmouth. I don’t think there were others.’”

Perhaps Ogden said it best. “Programming wasn’t an exercise in frustration anymore. It was fun.”

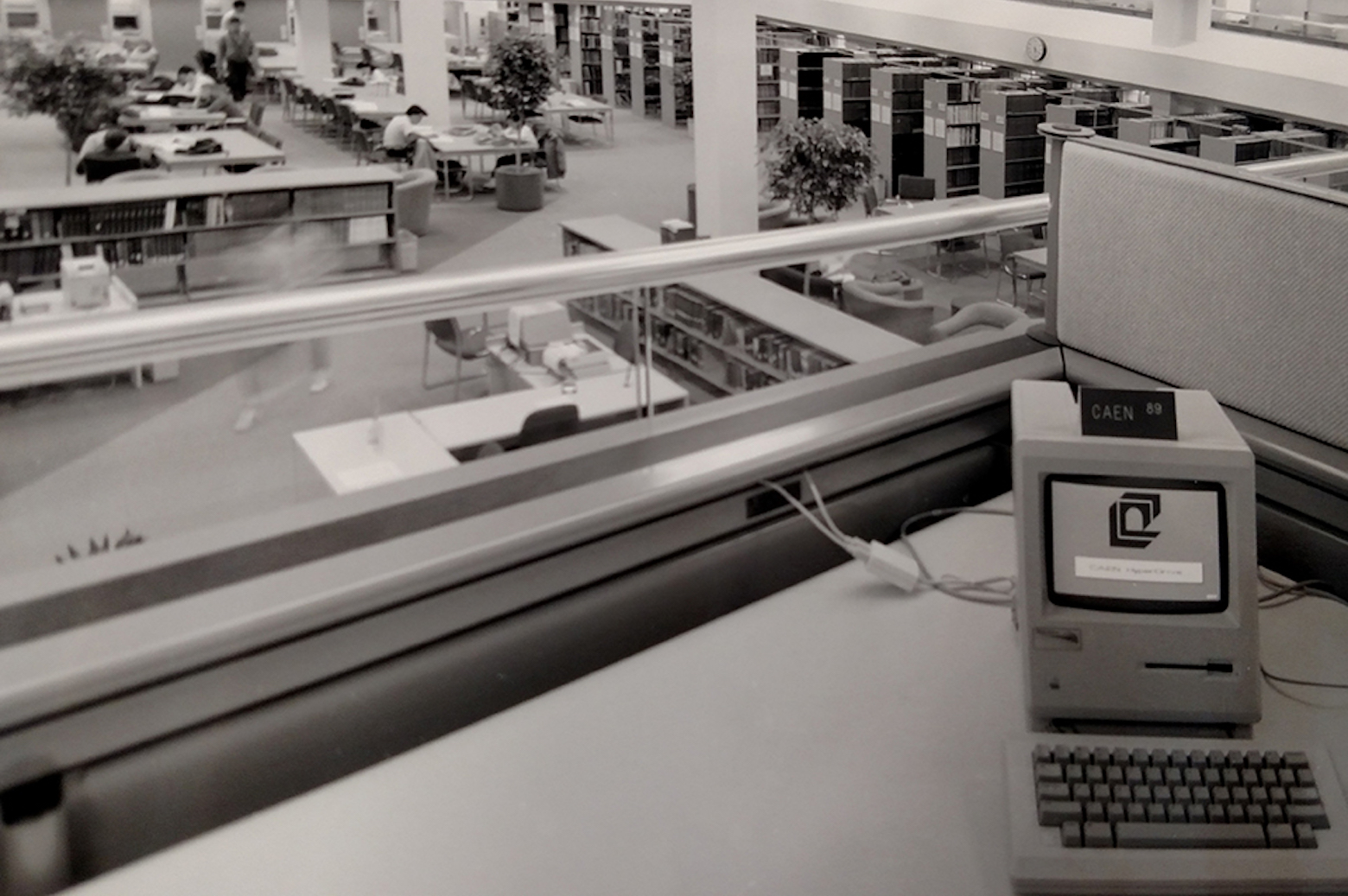

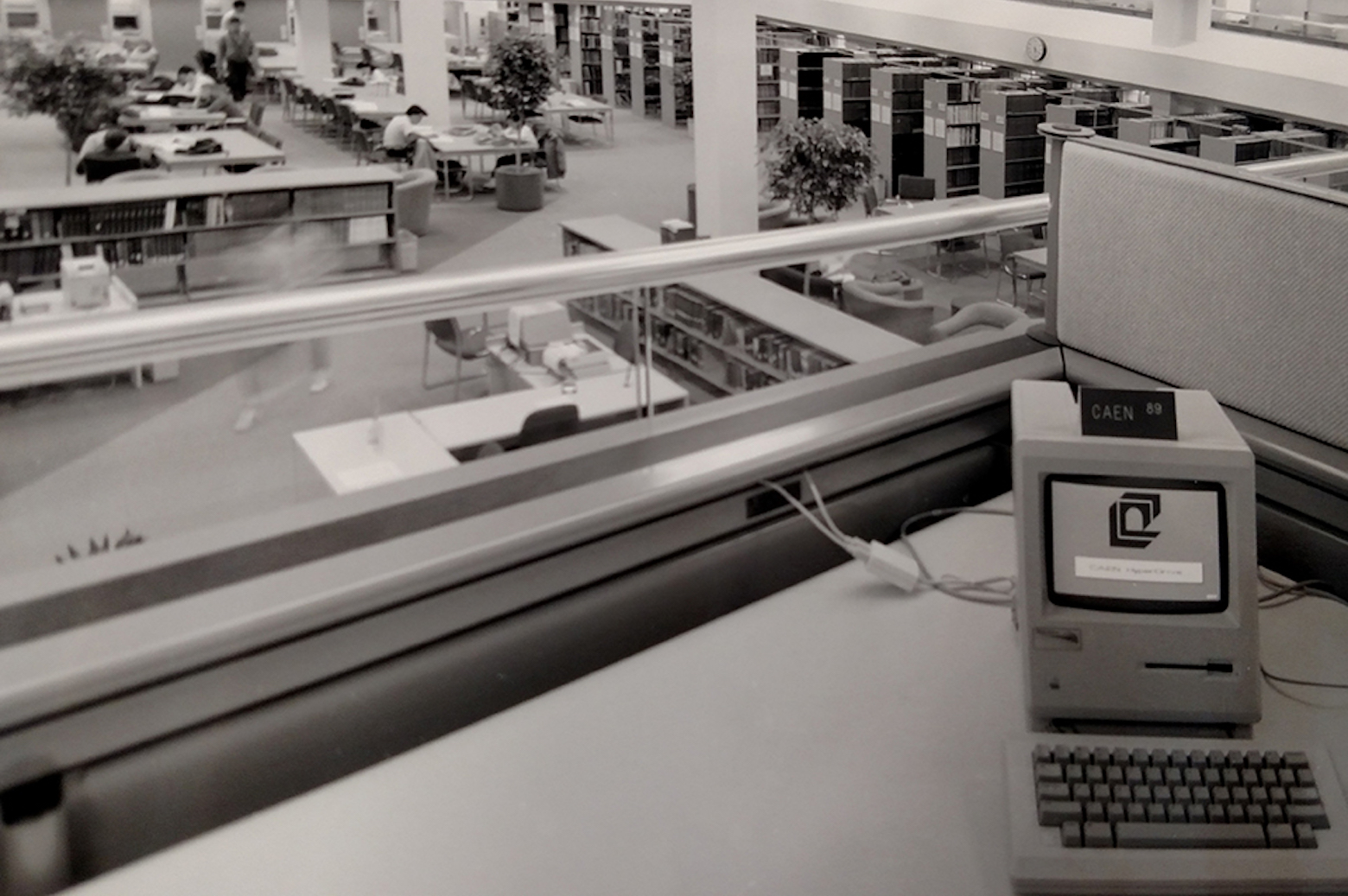

CAEN: A great time

Enlarge

Enlarge

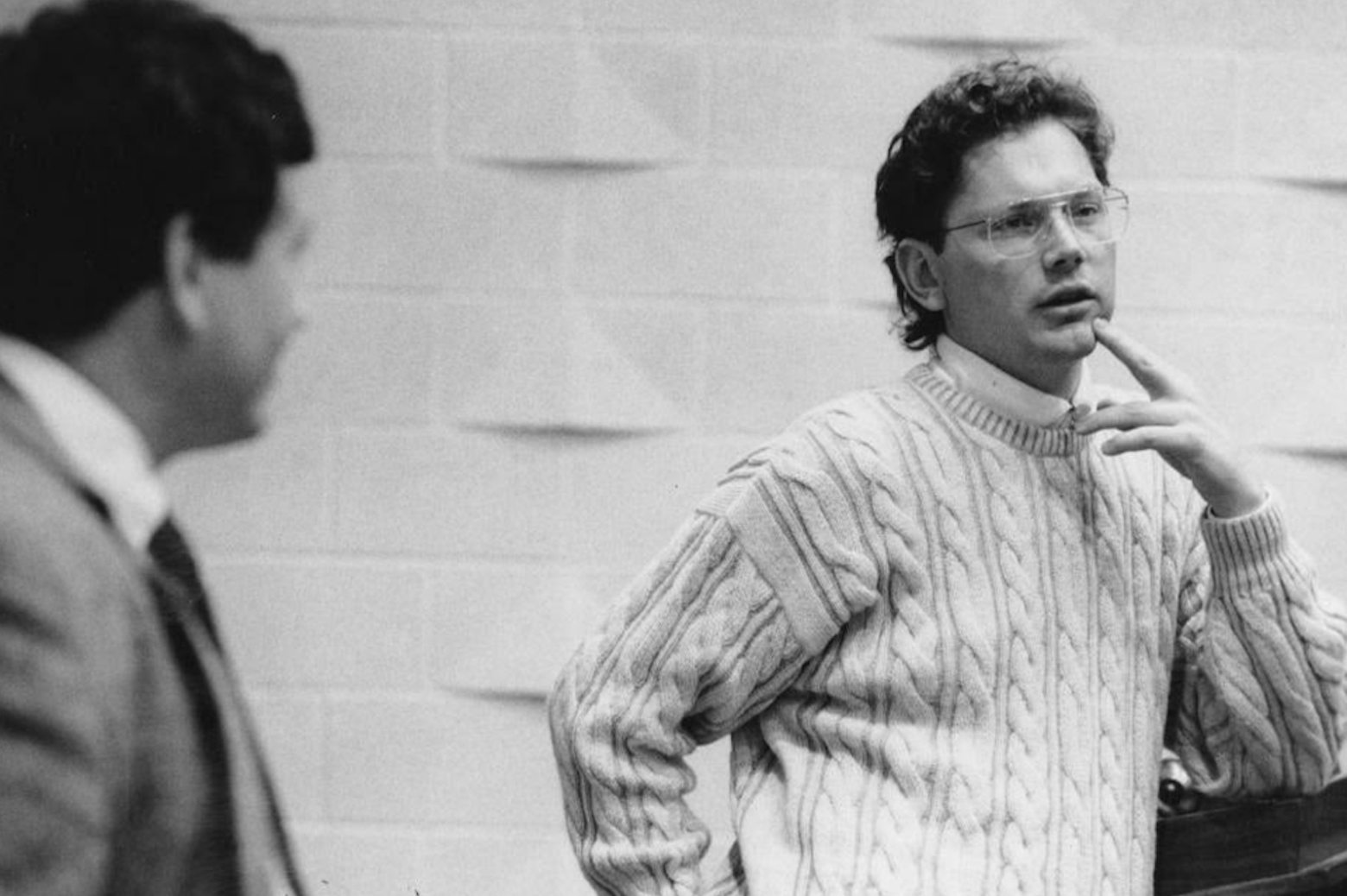

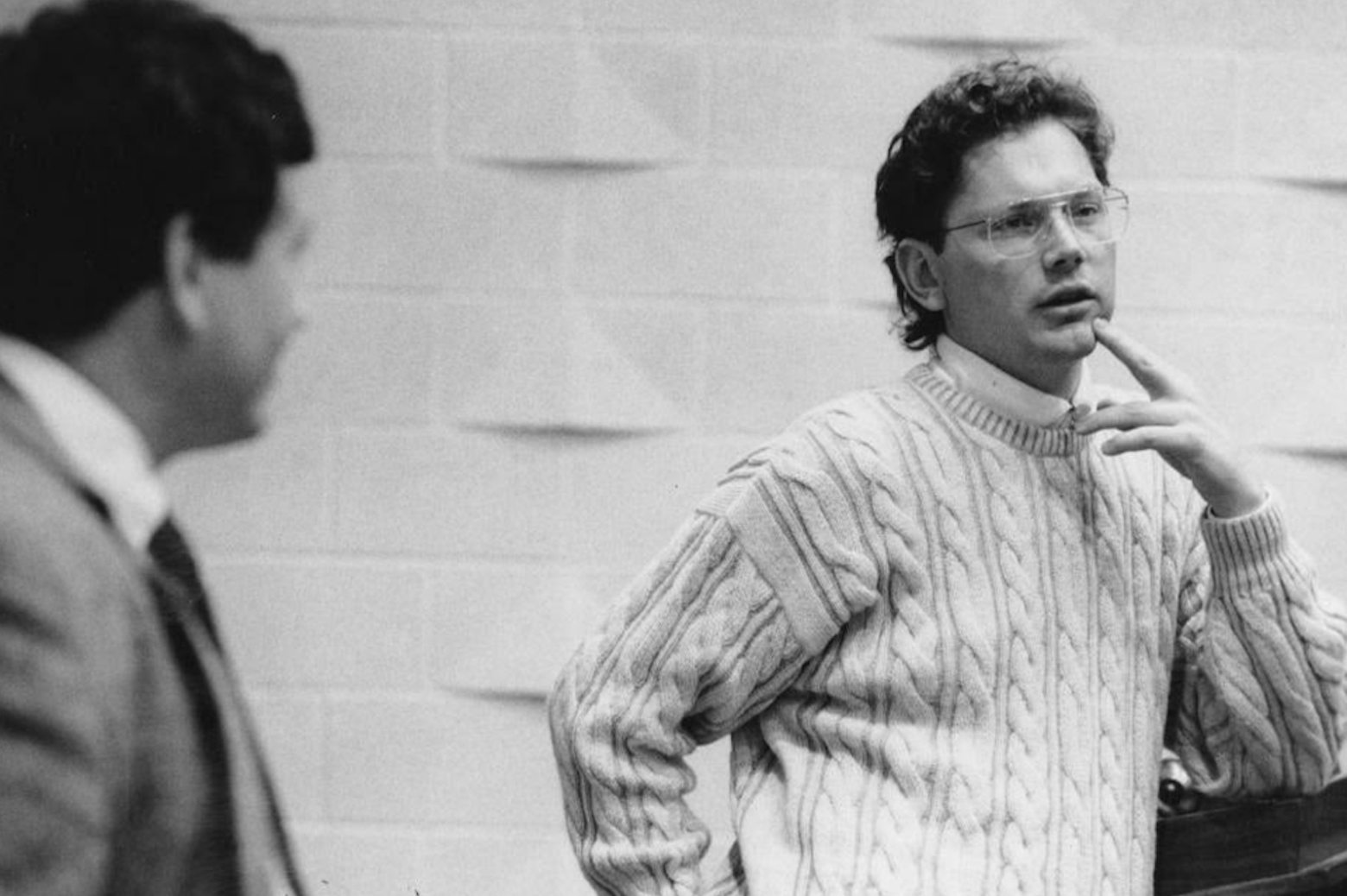

The 1980s brought a new round of leadership. Harold Shapiro was University president. Billy Frye was provost. And Douglas Van Houweling was recruited from Carnegie-Mellon as the new chief information officer, whose first order was business was to turn the U-M computer system into one unified community network.

The University was immersed in a $300 million effort, funded jointly by the state and the University, to turn the Michigan medical center into a national leader in clinical care and research. And James Duderstadt, then dean of Michigan Engineering, seized an opportunity to give its faculty and student body something no other college was yet providing – high performance computers.

The result was the Computer Assisted Engineering Network (CAEN) – and Atkins counts among his most significant accomplishments the decision to hire Randy Frank to direct it. In its first year, CAEN offered 100 Apple Lisa computers for open computing use by all engineering students in three separate labs (145 Chrysler Center, 2070 Dow, and the Engineering Library). Telnet services became available in 1988 and email usage became widespread by 1994 – which was also the year that marked the establishment of Camp CAEN, a “computer exploration camp” that introduced computer science engineering to middle and high school students.

Once high-powered engineering workstations were introduced, it didn’t take long for the revolution in how engineering design was taught, especially at the undergraduate level.

Enlarge

Enlarge

“We had more sophomore students doing complex integrated circuit design and mechanical engineering students designing complex mechanical systems that previously only arcane experts in industry were doing,” says Dan Atkins, professor emeritus of electrical engineering and computer science at the Michigan Engineering and professor emeritus at the School of Information.

And as early as the mid-1980s, “We not only put the computing in, we made significant, meaningful use of it and engaged in lots of curriculum modernization and reform. We weren’t only leaders at the University, we were leaders in the country’” Atkins adds.

CAEN was created to “provide faculty and students with state-of-the-art, risk-taking, cutting-edge technology,” and to “foster the use of technology in engineering research and learning” – and it did that and more.

Atkins says it also made Michigan’s engineering students more marketable, since they were entering the job market with experience dealing with “sophisticated design problems.” And the emergence of workstation computing would ultimately revolutionize engineering design.

This interactive timeline was developed in 2008 as part of CAEN’s 25th anniversary.

What’s changed?

Van Houweling’s answer to that question is, “Everything.”

“Libraries aren’t places you go to look up information anymore; they’re places you go to work on information – which is in the network. Faculty used to work primarily with people who were geographically close. Now they work with people all over the world.

“Back in the eighties, we thought of computers as mostly number machines. Now we no longer talk so much about computers as about information technology, because computers are the foundation of the way we organize and use knowledge. Today it would be impossible to think of a university without computing.

“If computers go down now? Nothing works! We can’t even open and close the doors in our buildings!”

“When I came to the University, if the computers went down for an hour or two, it was no big deal. If computers go down now? Nothing works! We can’t teach classes. I mean, we can’t even open and close the doors in our buildings!”

MENU

MENU